|

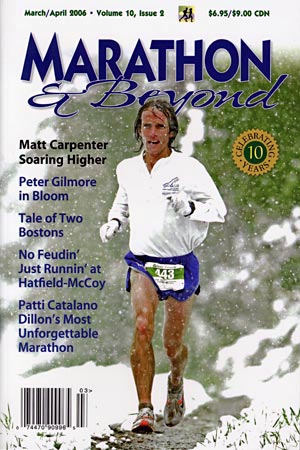

Marathon & Beyond - March/April 2006 - Volume 10, Number 2

Matt CarpenterDeviating from the Horizontalby Clay Evans Matt Carpenter doesn’t like to tie his shoes. Call him “loose school.” “That’s one thing I do differently than a lot of people: I never untie my shoes. I just tie them and slip them on and off,” he says. “Today’s shoes are so built up that if you tie them too tight, the shock is transferred to your knees and your hips. I like to have my foot move around in my shoe.” But what about those black toenails? If you’re going to be running up and down mountains, don’t you have to tie your hi-tech, ultrasupported shoes tighter than a bear trap to avoid those? “Look, if you’re getting black toenails, you’re overstriding,” Carpenter says patiently, his smile rarely fading. “You have to try to run efficiently.” There is more that might surprise people about the man who has been called the king of Pikes Peak. Carpenter, 41, has won the grueling Pikes Peak Marathon 11 times, holds records in three age groups and the overall course record-and he shattered the record at the Leadville Trail 100 in 2005, just a year after moving up to ultra distances. Carpenter wears cheap, ankle-high cotton socks and cotton T-shirts when he runs, and these days, more often than not, he is pushing his 4-year-old daughter, Kyla, in a heavy-duty running stroller. “I’m definitely old school,” says Carpenter, whose blue eyes, broad forehead, and high cheekbones give him a perpetually cheery expression.

A MOVE TO THE ULTRA SIDE

In Carpenter’s first official race beyond the marathon distance, he blew away Dave Mackey’s course record in the San Juan Solstice 50-Mile Run by 43 minutes, becoming the first person to finish in under eight hours, at 7:59:44. That finish, nearly two hours faster than the next-best competitor, earned Carpenter the moniker “freak of nature” from awestruck race organizers. “San Juan was really scary for me, so I was glad once the gun went off and we got running,” Carpenter says as he trots along behind the stroller on his way into downtown Manitou Springs, one of his short training routes. “But everything just really clicked that day.” The next logical target was a 100-mile mountain race. Just two months after Lake City, Carpenter took on the infamous Leadville course-and bonked, though a Carpenter bonk is still a prodigious finish by most standards. After a fast start, he walked the last third of the race, finishing 14th. Post-Leadville ‘04, he quickly identified his major problem: not enough recovery time. “If I had not done Lake City,” he said in 2004 the week after Leadville, “I could have won Leadville.” Some in the ultra community smirked at Carpenter’s “collapse": guy can do 50 miles, sure, but a 100 is a whole different universe. Some dismissed Carpenter as a one-hit wonder. But Carpenter himself was only emboldened. “There is a reasonable chance I will do [Leadville] again next year,” Carpenter said following Leadville ‘04. “One reason I didn’t want to quit is then I would definitely have to go back. I’ve done one, now. But I haven’t done one right . . . yet.”

A VO2 MAX FOR THE AGES He ran 20-mile segments of the course, experimented with different nutrition and hydration, and custom lightened his shoes.

“I ended up wearing no socks for San Juan, and my shoes I stripped, shaved rubber, and drilled holes in. There are 16 creek crossings at San Juan, and 1 thought, Tm not carrying all that weight uphill.’ I’ve always run in light, flexible shoes, and that day I just felt like an Indian,” he says. Following the race, he calculated that the amount of weight he shaved off his shoes saved him over 22,000 pounds of lifting. He is amazed that all the old-school fretting and fuming over weight doesn’t seem to concern today’s top runners. “We used to shave shoes, fold our numbers, cut ribbons in our shirts, but nobody does that any more. They just buy a pair of shoes right off the shelf,” he says. “But I think it’s crazy for people to think that some shoe made for average Joe, size nine, fits their feet just right. When I buy a shoe, the first thing I do is pull out the insole and stand in it to feel where it’s high or low; then I grind it out without the insole before I put it back in. A lot of insoles these days are so soft that they disguise imperfections of seams, low spots. Then, as it wears down, people wonder why they get sore feet and injuries.” But if Carpenter’s San Juan finish astonished the ultrarunning world-some openly wondered whether he was poised to become a Tiger Woods of the sport overnight-it still wasn’t a perfect race. His wife, runner Yvonne Carpenter, was his only crew member, and while that worked out for the best, there were unforeseen complications. “I made a few stupid tactical errors, just really dumb. I like to take PowerBars and dissolve them in water [bottles]. It tastes great, you get 250 calories, and if you try to eat at altitude, you spend too many calories and you can go into oxygen debt,” he says. “But the bottles [of the PowerBar/water mix] that I set out at the aid station congealed and started to ferment. I had to drink that crap for nine miles at 12,000 feet. That really did wonders for my tummy.”

PIKES PEAK IS ONE THING, BUT 50 MILES? “The reaction fell into two categories,” Carpenter recalls. “Some people said I was going to do what I did, break Mackey’s record. The other camp said I’d drop out or end up in the hospital.” And when Carpenter turned in his record-crushing performance on June 19, it looked like his somewhat unorthodox attitude toward training for an ultra had paid off. “I have this theory that too many ultrarunners are doing too much long stuff,” Carpenter said before Leadville ‘04 as he kept an eye on Kyla at a park near his home in Manitou Springs. “They aren’t doing the quality. That’s probably because long running is kind of fun. “I think a lot of ultrarunners think because they are running longer, they should make their speed [workouts] longer. Look at the definition of a tempo run, raising your lactic acid to the threshold point. They suddenly think they need to do 40 or 50 minutes of speed workout. But you can’t run fast for that long. So I cut my speed workouts. They haven’t gotten any longer [than training for Pikes or other subultra events]. If I want to do more, I’ll do a double set. “So you have quality on one side, and quantity on the other. Don’t run too long and hard. Run long, or short and fast, and do recovery. Every workout has to have a purpose. I think a lot of ultra people are making mistakes in that area. You look at [Dave] Mackey, he’s emphasizing his quality. That’s why he’s been so successful,” Carpenter says. Shaved, drilled shoes; no socks; murky, fermented glop to drink; and a training schedule that some said would leave Carpenter begging for mercy at Lake City. Didn’t happen. But then came Leadville, and the whispers that he couldn’t cut it in a real ultra. “It’s a little irritating,” Carpenter says, though still beaming. “At every level, someone can say it’s not quite the real thing. No matter how well you do, there’s always a next level. You do a 100, and someone will say you’ve got to prove yourself at something longer,” like the 64-day, 3,000-mile Trans-America Footrace from Los Angeles to New York.

AGE TAKES ITS TOLL “Now my fastest times are probably behind me, except for in the ultra. I can say I’ve done some good things, but I’m never totally satisfied, but at the same time I’m getting to the point where I don’t want to grow older and wonder what might have been,” he said, explaining his decision to move into ultra running in 2004. “I’ve always had a bit of the extremist in me, and I think the ultra is more about attitude than anything. You’ve got to take the punches as they come.” And so, after Lake City, he did what Matt Carpenter does-focus on the next challenge, the storied Leadville Trail 100, every step of the mind-bending course higher than 9,200 feet, with a high point above 12,600 feet. He waited to enter until mid-August-in part because he felt a little shy about asking for a free entry, which he didn’t get, in the end-but almost from the moment his name went up on the race Web site, the e-mails started flying. The guy who blew away the Lake City record was stepping up. Would he be a serious threat, or just a poseur? Carpenter himself set seven progressively simpler goals he felt were possible at Leadville: break 16 hours on the course (the record is just under 18); break 17 hours; set the course record; win; set the masters course record; win the big belt buckle for under-24-hour finishers; and finally, no matter what, even if he couldn’t achieve any of those lofty ambitions, he simply wanted to finish. “I have the same attitude about training going into Leadville as I did before San Juan,” Carpenter said just a week before the 2004 race. “I know where things stand. I have my goals.” Matt Carpenter has been a runner for most of his life, and always competitive. But all the way through college, he always felt like he was developing too late. “The way I always kind of defined my career was that a year after high school, I would have been a really good high school runner. About the time I was getting out of college, I would have been a really good college runner. But because I was later in developing, I kept at it. Amazing guys that I ran with are no longer running, and for all I know, I might have gotten my fill in college. How good I was was never answered,” he says. His early years were difficult. He never knew his father, and he moved around a lot with his mother, who suffered from lupus. After his mother was transferred to Mississippi, Carpenter started seriously running for his high school cross country team.

THE LONGER THE BETTER Carpenter’s mother killed herself when he was 18, leaving him to fend for himself. But he won a full-ride track scholarship to Southern Mississippi: “Running became my way to get through college. I was drawn to the fact that it’s such a ‘you’ sport; you are in control of every aspect. It quickly became the only thing in my life that I was in absolute control of: how long I was going to run, if I was going to run, and why.” In hindsight, Carpenter thinks part of his psychological motivation to keep running was the haunting sense of an absent father and a mother who left him alone in the world. “I think maybe I was always trying to show [my father] that he shouldn’t have given me up. I had a lot of anger about it,” he says. “It was the same with my mom. For years I ran a lot of mountains, and I’d scream up at her, ‘I think you’d be proud of what I’ve done.’” But growing up with so much uncertainty may have had an unanticipated side benefit: “I think, with few exceptions, most athletes at the top level are paranoid and insecure. A lot of the training and running I’ve done because I never believed I was that good.” In 1983, he moved to Vail, Colorado, where he ran the Piney Creek Half-Marathon. “Right there, a ‘hill’ was defined for me. In Mississippi, a hill was going over railroad tracks. This course had switchbacks, and I kept thinking, ‘It’ll end around the next one.’ It didn’t,” Carpenter recalls, laughing. “I thought my heart was going to explode. But I’ve been hooked on trail running ever since.”

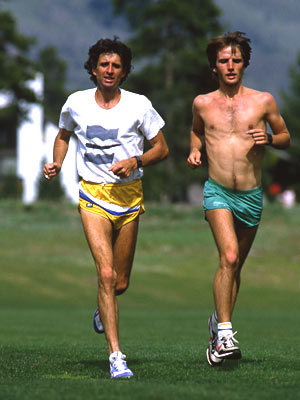

CONNECTING WITH FRANK Vail is also where he met Olympic marathon gold- and silver-medalist Frank Shorter.

“He told me he trained for his gold in Vail and for his silver in Boulder,” Carpenter says. In Vail, Carpenter helped pull together a local running club-never officially named, he says-and they built a 400-meter grass track. “I’ve always liked getting people together to run. It was the same thing in Vail [as with the Incline Club], all abilities. I was seldom running with the [more casual] runners, but having them out there made us all run better.” And living at altitude was paying off. As a scholarship level NCAA runner, Carpenter had registered a VO2max of 57 or 58, he recalls. “Not too special. They said it was an all-right number and that it was all about genetics. But then I went up to Vail and ... in 1992 I went to the Olympic Training Center [in Colorado Springs] and registered the 90.2,” he says. “So, then they told me, ‘It’s genetic that you improved so much.’ I began to learn that pretty much every test we did was all about genetics. It kind of irks you to hear, when you know how much training goes into it.” His father tracked him down a few years ago, and if Carpenter’s abilities are genetic, there are no particular clues there: “He lettered in four or five sports but didn’t consider himself good in any.” Eventually, Carpenter chose Manitou Springs over Boulder as the right place to settle and train, and in 1987 he first entered his signature race, the Pikes Peak Marathon. (Pikes Peak has never given up its self-proclaimed status as “America’s Ultimate Challenge"; it’s a tough race, to be sure, but in the days of Leadville and Western States, that’s an overstatement.) “I ended up fourth [behind Chester Carl],” Carpenter writes in his book, Training for the Ascent and Marathon on Pikes Peak, with co-author Jim Freim. “As I lay on a stretcher downing my energy drinks, bananas, and grapes, I felt relief. Relief that I was no longer running.” But he has kept running the lung-busting race ever since, winning 11 out of the 16 times he’s run either the Pikes Peak Marathon or the Pikes Peak Ascent. He owns age-group records for 20-24, in 1988; 25-29 (a course record 3:16:39 that still stands today) in 1993; and the 35-39 record in 2003.

LEARNING EVERY ROCK AND ROOT “Pikes is right on the edge. If you train the right way, you can run the whole thing. Of all the ones I’ve done, it’s still my favorite course in the world. It’s got the huge megagain; it’s got the altitude. But it’s not what I would call extreme.”

Thousands of participants surely beg to differ, but it’s true that, despite his rep on Pikes, Carpenter has done much harder races and events all around the world. Based on his Pikes Peak dominance, he won sponsorship from Fila in 1993 to compete in the Mount Everest Marathon in Nepal and Tibet. “I had no idea there was money in this at the time,” he says. “I thought it was amazing that somebody would pay your way to Nepal and Tibet just to run.” That first time he ran in Asia, Carpenter’s reputation preceded him. Other runners came up to him and declared him all-but-the-winner of a $5,000 purse. “Dang,” he remembers thinking, “this is a real sport.” Altogether, Carpenter did five Everest runs from 1993 to 1998, winning every time. With the Sky Runner-sponsored races, he also ran in Europe and elsewhere, including a race in Italy that featured a vicious 11,000-foot gain in just nine miles. In his spare time, Carpenter also helped found the Incline Club of Manitou Springs with Larry Miller and Tom Santa Maria. Originally, the club was formed to run the absurdly steep incline just west of the town-unsurprisingly, Carpenter holds the record for that mile-long ascent, too-but now conducts regular runs year-round on Thursdays and Sundays, often training on the Barr Trail in preparation for the Pikes Peak races. Members run to the A-frame at the halfway point seven or eight times a year, Carpenter says, and make the round trip three or four times a year. The group’s mottoes are “Deviate from the horizontal” and “Go out hard. When it hurts, speed up!” “The Pikes Peak Marathon dubs itself as the ultimate challenge. Well, we like to do the ultimate challenge ... as a training run,” Carpenter says, clearly relishing how casually-and honestly-he can say that.

KEEPING THE REP ALIVE And Carpenter’s relationship with his signature race has not always been comfortable. He has boycotted several years-not because he was out of shape or untrained or injured, but because he objected to the way the race was being run, particularly regarding overstringent rules that kept top runners out and reduced the competition. A new race director, Dave Zehrer, arrived in 1996 and promptly eliminated course-record bonus prizes. Zehrer also killed off the two other legs of the “Triple Crown of Running” and declared that, as a citizen’s race, the Pikes Peak Marathon would no longer make exceptions for entry by top competitors when the race was full. “He just wasn’t letting people in. Barbara Reimers won Mount Washington one year only training on a treadmill in New York City. She wrote the Pikes director asking if she could get in the Ascent, and he wouldn’t let her,” Carpenter says. “He said it’s not fair to hold out a [citizen] runner just because some fast guy gets in.” For taking that position publicly in letters to the editor calling for Zehrer’s resignation, Carpenter was labeled a greedy elitist by some. But for him, it was all about competition, the level of which had plummeted on Pikes Peak so that winning times were no better than those of the 1960s. “When I run a race and see a fast athlete, I am awed and inspired. If you can’t get excited about that, you are dead,” he says. Partly in protest of the Pikes policies, Carpenter helped start the Barr Trail Mountain Race, which ventures about halfway up the Pikes Marathon course and back. The race holds final spots open until the last three days, encourages local high school teams to participate, and gives thousands of dollars back to prep athletes. Eventually, Zehrer was replaced as Pikes Peak’s race director. Today, with a new committee and a new board, the Triple Crown has been resurrected, the competitiveness on Pikes has surged, and the marathon and ascent hold 40 spots each for top runners until almost race day. “Tons of athletes complained, and things changed,” Carpenter says. Eventually, Carpenter was ready for new challenges. He originally planned to run Leadville at 39 and at 40, seeking to set age-group records, but becoming a father intruded on that lofty goal. In addition, he failed to take a back injury seriously enough a few years ago, and that threw him off his stride.

GIVE THE BACK A REST It took him a year to come back. But leading up to San Juan ‘04, he was running two hours a day, and for six months straight he had no days under an hour and a half. Prior to Leadville, he was running 13 hours a week, he says-"10 of them with the baby jogger.” Training for the 2004 San Juan 50 helped Carpenter realize he had lost some of his buzz for running, and also helped to renew it. “It brought back the spark for me. It’s neat to love it again. The only thing keeping me going for a number of years was the Incline Club,” he says. Training for his first 100, Carpenter stuck with his philosophy that too many ultrarunners essentially overtrain. Because 40-mile runs were “wasting” him, keeping him from doing his quality/speed workouts later in the week, he kept longer runs down to 25 miles. “I’d run 25 and 25, back-to-back. The second day I was tired, running tired, which better simulates what happens in a [100-mile] race,” he said before Leadville ‘04. He paused for a minute, turning his eyes toward the horizon to the east. Then he smiled. “Well, it worked for me in Lake City, but until the rubber hits the dirt, it’s just a theory for Leadville,” he said. He went out strong in the 2004 Leadville Trail 100, leading the pack of about 500 runners for the first 60 miles and staying near the lead right through 67, through freezing rain, hail, and dark of night. But he knew something wasn’t right early on. “When I pulled into May Queen [campground] at only 13.5 miles, I already told my crew I was scared,” he said three days after the race. “And when I got to the Fish Hatchery [mile 23.5], I started taking aspirin. By Treeline [28], I told them I did not see how I was going to be able to finish, as my quads were just shot.”

THE LONG WALK BACK Paul DeWitt won the 2004 race for a second year in a row, coming in at just under 18 hours, and Scott Jurek, considered by many to be the best American 100-miler, finished his first LT 100 in 18:01. Dave Mackey, whose own first foray into quad-killing 100-mile competition came out somewhat better-he finished second at the 2003 Western States race in June-said Carpenter would get the hang of 100s if he decided to stick with it. “I was one of those people who thought he would go in and kick ass [at Leadville],” Mackey said. “There’s something physically he hasn’t figured out yet about doing a 100. ... It’s hard to predict how your body’s going to react. There may be a longer-term adjustment, a cellular physical change, to those kinds of races. Maybe everybody’s first 100 completely sucks.” Carpenter’s body was battered and would take months to fully heal, but he remained philosophical. “It wasn’t the best debut, but there certainly are a lot worse debuts than mine,” he says. And he had no doubt about what killed him: “I’ve got to realize that Lake City took a lot out of me, and I just never fully recovered,” he said after Leadville ‘04. In an e-mail sent the day after the race, Carpenter considered what was most important about the experience: “As far as finishing, I can honestly say I am not happy that I finished. However, I am extremely happy and proud that I did not quit. That may seem contradictory, but I am just being honest. From [mile] 55 on I was running on tendons and bones, as my quad muscles could no longer support me ... I did not quit, and I can hold my head high.” But Matt Carpenter runs for a lot more than pride, as the 2005 Leadville field discovered. Remember those goals Carpenter set for himself at Leadville in 2004? Break 16 hours (on a course where the record was set by Paul Dewitt in ‘04 at 17:16:19); break 17 hours; set the course record; set the masters record; win a “big” belt buckle for a finish under 24 hours; and finally, no matter what, just finish. In 2004, he knocked off the last two items, but all those other lofty ambitions egged him on to enter Leadville in 2005. Plus, he figured, it wouldn’t hurt to prove his naysayers wrong. And boy, did he. Matt Carpenter ran nearly every foot of the course (except for a couple of creek crossings), an almost unheard-of feat, and crossed the finish line in 15:42:59, busting the course record by more than an hour and a half. His accomplishment has some people guessing that he will be named ultrarunner of the year, or at least recognized for best performance of the year.

THE SECRET LEADVILLE TRAINING

Among those tweaks: Carpenter ran without pacers in the ‘05 race (“That way, I could focus on just myself); pointedly did not run on the course beforehand; and bumped up his daily runs from an hour and a half to two hours. “Getting beat like that gave me incentive. I said, ‘OK, two hours is what I used to do at my prime. I have to train like I used to train,’” he says. “I wouldn’t have done that if 13 people hadn’t waxed my butt at Leadville last year.” Carpenter is more convinced than ever that he has hit upon a flaw in many ultrarunners’ training: too much distance. “I think with the extreme damage you cause, you’ve really got to recover,” he says. The ‘05 race was “like a dream,” Carpenter says. But it took courage to go out even faster than he did in 2004, when it took a supreme act of will just to stagger those last 33 miles to reach the finish line. “That was the hardest part, having the confidence to go out even harder after what happened last year,” he says. But when he passed cruel milestones from the 2004 race, it didn’t bother him. “I remembered where I was falling apart last year, where I was sitting down .... This year, it was comical: ‘Oh, my God, here’s that bridge.’ I was flying again. It was really fun. I’m so glad I didn’t do any training [on the course] over there.” Carpenter feels vindicated after having figured out what held him back in 2004: “Nobody wanted to believe me that the problem was everything was left at Lake City [in 2004]. Some people were making fun of me.” They aren’t now. But, of course, some people will never be satisfied. Carpenter has seen Internet posts from runners who apparently want to tarnish his effort again. “It’s funny to read those posts. People say, ‘Oh, he’s run all his life, he runs three times a day, he has no life.’ It’s strange, but you get used to it. The ultra world is a little different in that respect; there’s a lot of talking.”

WHAT WILL BE THE NEXT CHALLENGE? But he’s not going to make any decisions on anyone else’s timetable. For one thing, ultras don’t pay: Carpenter hauled in about $5,000 for four shorter races previous to Leadville ‘05, which ended up costing him about $1,000. “I had personal reasons for doing Leadville again. Now I’ve done it and gotten some kind of redemption. I’m not ruling out [more ultras], but right now I’m not looking that far ahead,” he said in October. “But I’ve got to look into some kind of sponsorship. I don’t have anything to prove that I have to pay to run.” |

Back to Bio